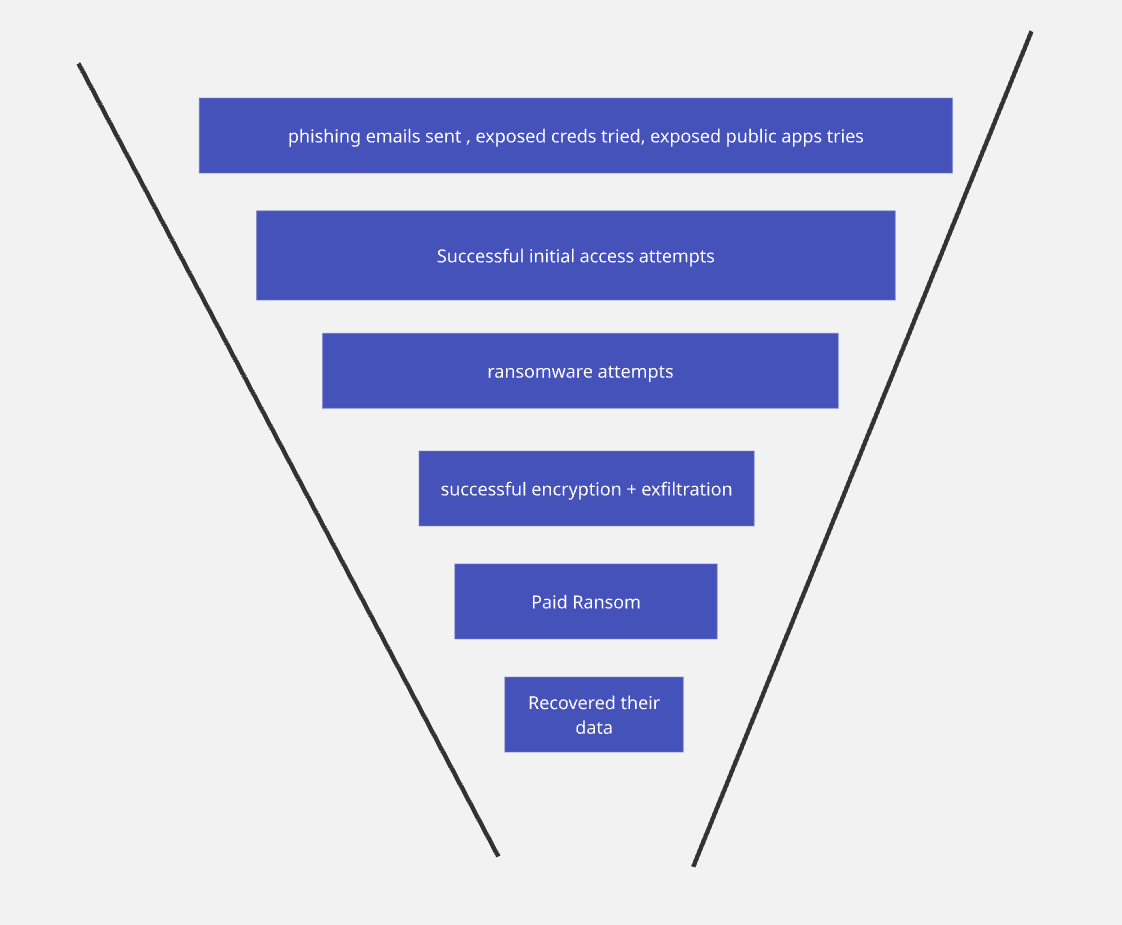

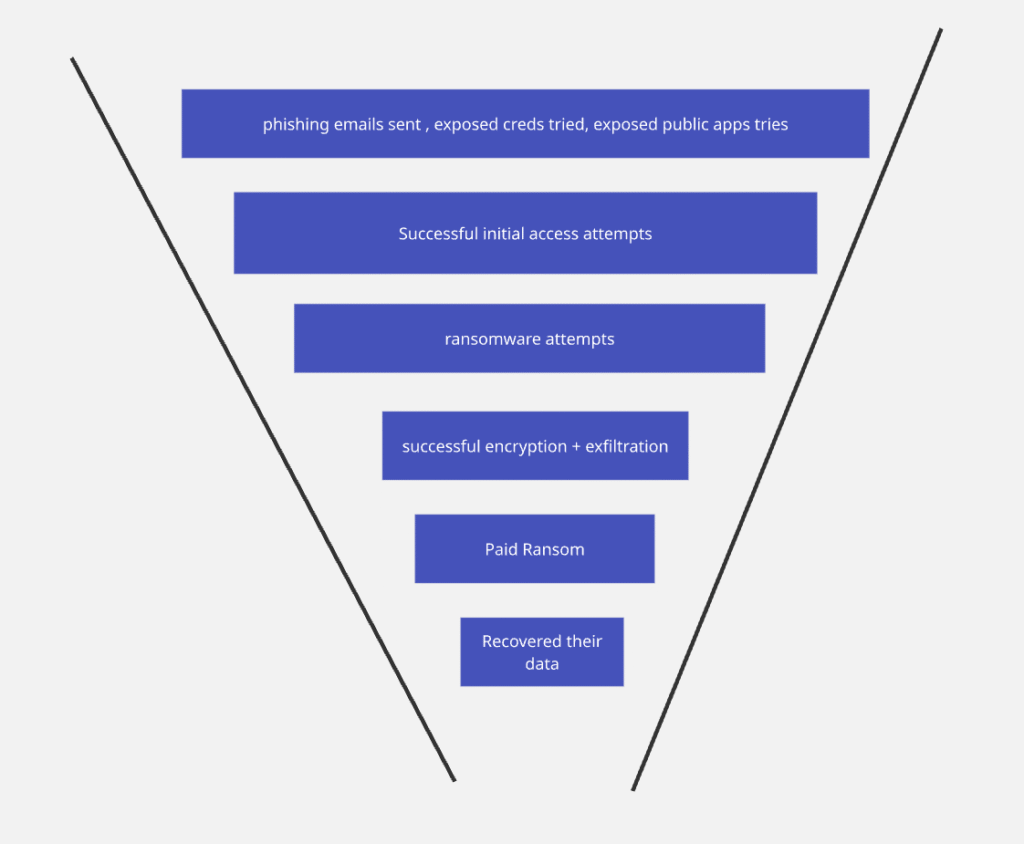

Imagine the classic sales funnel: thousands of visitors, dozens of leads, a handful of conversions, and — if your marketing is decent — a few paying customers. Now swap the “marketing team” for organized cybercriminals and the “product” for encrypted data. Strange? Not really. Welcome to the Ransomware Funnel.

This is not a metaphor for shock value. It’s a scientific framing: attackers optimize throughput, measure conversion rates, and prioritize high-value targets — exactly like a corporation. Understanding their funnel maps directly to where defenders should spend resources to reduce the attacker’s conversion rate. Business language, universal logic, zero techno-babble. Let’s break it down.

1. Top of Funnel — The Noise (Prospecting at Scale)

Phishing emails, credential spraying, and automated scans of publicly facing apps make up the flood at the funnel’s wide mouth. From a statistical perspective this is a high-volume, low-cost phase: attackers send huge numbers of probes because even a tiny click or reused password yields disproportionate value.

Scientific principle: power law + scale. A tiny positive-tail probability multiplied by massive scale equals consistent returns. In plain English: spam enough mail and one bored, tired, or distracted human will click. That single click is all an attacker needs to start the rest of the pipeline.

Funny truth: it’s like a telemarketer who got rich because one person thought they were calling their mom.

2. Initial Conversions — The Foothold (First Contact)

When an employee clicks a malicious link, an exposed credential works, or an old server answers a probe — attackers gain a foothold. This is an asymmetric event: a single successful conversion changes the defender’s state massively.

Scientific principle: asymmetric attack vectors. Small inputs (one click) produce large state changes (access). From a risk-management view, this is where probability meets impact.

Human note: this stage looks suspiciously like when someone actually fills out a demo form — except here, the demo installs ransomware.

3. Mid-Funnel — Ransomware vs. Other Monetization (Prioritization)

Not every compromise becomes ransomware. Attackers triage: some access is sold, some is used for cryptojacking, some becomes reconnaissance for later attacks. A portion, however, is escalated into ransomware — either opportunistically or after reconnaissance shows promising value.

Scientific principle: resource allocation. Attackers allocate their limited “payloads” where expected ROI is highest. They run cost–benefit calculations (albeit ugly, illegal ones) and focus on evidence-backed targets.

Comedy aside: criminals do triage spreadsheets. Imagine a spreadsheet called “C2 Leads — Q3” — horrifying and almost corporate.

4. Qualified Leads — Successful Ransomware Attacks (Filtering & Detection)

Many ransomware attempts are detected, sandboxed, or rolled back by security controls. The funnel narrows. The attackers that get through are those who bypass detection — by timing, privilege escalation, novel payloads, or credential misuse.

Scientific principle: defense-in-depth & signal-to-noise. Each detection layer reduces the attacker’s conversion probability. The more independent layers you have, the closer you get to multiplying down the attacker’s success rate.

Human truth: think of it as multiple bouncers — every additional security control is another “no” before the attacker reaches VIP access.

5. Closed Deals — Paying Ransoms (Economics of Extortion)

When data is encrypted and exfiltrated, victims face a decision: pay, negotiate, or refuse. Industry reporting indicates that many organizations refuse or only partially pay — outcomes vary widely. Paying is not a guarantee of full recovery; sometimes the decryption is buggy, sometimes data is leaked anyway.

Scientific principle: incentive alignment (or misalignment). Paying rewards the criminal business model and can increase incentives for future attacks; refusing increases immediate impact but may reduce long-term incentives for criminals. Both choices change future expected values for the defender.

Real talk: paying a ransom is like trying to get a refund from a shoplifter — possible, but weirdly untrustworthy.

6. Customer “Success” — Data Recovery (Uncertain Outcomes)

Even after payment, the success curve is messy. Some organizations regain operations; others only get partial recovery or become victims of repeat extortion. The recovery stage highlights that attacker ROI is not binary: partial successes are still profitable.

Scientific principle: stochastic outcomes — the event of paying does not deterministically produce recovery; it’s probabilistic and noisy.

Human summary: you might get your files back. Or not. It’s like ordering a replacement part from a pirate — sometimes it’s a perfect fit; sometimes it’s a bootleg USB shaped like a brick.

Why Executives Should Care — The Business Case in One Line

A tiny conversion rate from the top-of-funnel noise can translate to catastrophic losses. The funnel reframes cybersecurity as conversion-rate management: reduce exposure, reduce footholds, increase detection — and you throttle the attacker’s business model.

Scientific principle: leverage and marginal effect. Small improvements early in the funnel multiply downstream. Stopping a single phishing click prevents all downstream losses associated with that compromise.

The Short, Non-Boring Takeaway

Ransomware is industrialized. It’s organized, measured, and optimized. Treat it like a business problem: quantify the funnel, reduce conversion rates at the cheapest early stage possible, and report expected value improvements to the board in plain business terms. The more we think like defenders and like analysts, the more we turn the attacker’s funnel into a leaky, ineffective pipe.

And hey — if you still want to argue with a criminal spreadsheet, at least make sure your backups are offline, your MFA works, and your CISO has coffee.